Most households only use one or at most two different rubbish bins, one for recyclables (paper & packaging) and one for general waste. It makes a lot of sense to add a third type of rubbish bin, for biowaste, i.e. kitchen waste, soil and garden waste.

Many people already compost such biowaste in the garden, but all too often such biowaste disappears along with the general waste in the rubbish bin. As displayed on the picture below, analysis in Waikato, New Zealand, shows that about half of household waste can consist of kitchen waste, soil and garden waste. Such waste ends up on rubbish tips, where the decomposing process leads to greenhouse gases, such as methane. And all too often, farmers burn crop residues on the land, resulting in huge emissions of greenhouse gases.

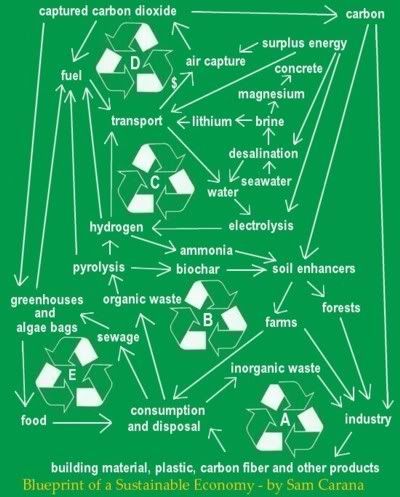

All such biowaste could deliver affordable energy by using the slow burning process of pyrolysis to produce agrichar or bio-char, a form of charcoal that is totally black. Organic material, when burnt with air, will normally turn into white ash, while the carbon contained in the biowaste goes up into the air as carbon dioxide (CO2). In case of pyrolysis, by contrast, biowaste is heated up while starved of oxygen, resulting in this black form of charcoal.

This agrichar was at first glance regarded as a useless byproduct when producing hydrogen from biowaste, but it is increasingly recognized for its qualities as a soil supplement. Agrichar makes the soil better retain water and nutrients for plants, thus reducing losses of nutrients and reducing the CO2 that goes out of the soil, while enhancing soil productivity and making it store more carbon.

When biowaste is normally added to soil, the carbon contained in crop residue, mulch and compost is likely to stay there for only two or three years. By contrast, the more stable carbon in agrichar can stay in the soil for hundreds of years. Adding agrichar just once could be equivalent to composting the same weight every year for decades.

Agrichar appears to be the best way to bury carbon in topsoil, resulting in soil restoration and improved agriculture. Agrichar has the potential to remove substantial amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere, as it both buries carbon in the soil and gets more CO2 out of the atmosphere through better growth of vegetation. Agrichar restores soils and increases fertility. It results in plants taking more CO2 out of the atmosphere, which ends up in the soil and in the vegetation. Agrichar feeds new life in the soil and increases respiration, leading to improvements in soil structure, specifically its capacity to retain water and nutrients. Agrichar makes the soil structure more porous, with lots of surface area for water and nutrients to hold onto, so that both water and nutrients are better retained in the soil.

In conclusion, recycling biowaste in the above way is an excellent method to produce hydrogen (e.g. for cars) and to bury carbon in the soil and improve production of food. Agrichar is now produced for soil enrichment at a growing number of places. The top photo shows agrichar in pellet form from Eprida. Australian-based BEST Energies has built a demonstration pyrolysis plant with a capacity to process 300 kilograms of biowaste per hour. It accepts biowaste such as dry green waste, wood waste, rice hulls, cow and poultry manure or paper mill waste. The plant cooks the biomass without oxygen, producing syngas, a flammable mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. The agrichar thus produced retains about half the carbon of the original biowaste (the other half was burned in the process of producing the syngas).

Also important is to compare different farming practices. Carbon is important for holding the soil together. Farmers now typically plough the soil to plant the seeds and add fertilizers. This ploughing causes oxygen to mix with the carbon in the soil, resulting in oxidation, which releases CO2 into the atmosphere. Ploughing leads to a looser soil structure, prone to erosion under the destructive impact of heavy rains, flooding, thunderstorms, wind and animal traffic. Given the more extreme weather that can be expected due to global warming, we should reconsider practices such as ploughing.

Furthermore, the huge monocultures of modern farming have become dependent on fertilizers and pesticides. The separation of farming and urban areas has in part become necessary due to the practice of spraying chemicals and pesticides. Instead, we should consider growing more food on smaller-scale farms, in gardens and greenhouses within areas currently designated for urban usage. Vegan-organic farming can increase bio-diversity; by carefully selecting complementary vegetation to grow close together, diseases and pests can be minimized while the nutritional value, taste and other qualities of the food can be increased.

An issue of growing concern is nitrous oxide (N2O), which is 310 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas when released in the atmosphere. Much release of N2O is related to the practices of ploughing and adding fertilizers to the soil. Microbes subsequently convert the nitrogen in these fertilisers into N2O. A recent study led by Nobel prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen indicates that the current ways of growing and burning biofuel actually raise rather than lower greenhouse gas emissions. The study concludes that growing some of the most commonly used biofuel crops (rapeseed biodiesel and corn bioethanol) releases twice the amount of N2O, compared to what the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates for farming. The findings follow a recent OECD report that concluded that growing biofuel crops threatens to cause food shortages and damage biodiversity, with only limted benefits in terms of global warming.

All this is no trivial matter. Soils contain more carbon than all vegetation and the atmosphere combined. Therefore, soil is the obvious place to look at when trying to solve problems associated with global warming. By changing agricultural practices, we can add carbon to the soil and can minimize release of greenhouse gases.

References:

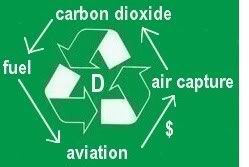

Additionally, the aviation industry can offset emissions, e.g. by funding air capture of carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide thus captured could be partly used to produce fuel, which could in turn be used by the aviation industry, as pictured on the left. The carbon dioxide could also be used to assist growth of biofuel, e.g. in greenhouses.

Additionally, the aviation industry can offset emissions, e.g. by funding air capture of carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide thus captured could be partly used to produce fuel, which could in turn be used by the aviation industry, as pictured on the left. The carbon dioxide could also be used to assist growth of biofuel, e.g. in greenhouses.

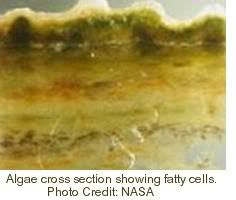

Apart from growing algae in greenhouses, we should also consider growing them in bags. NASA scientists

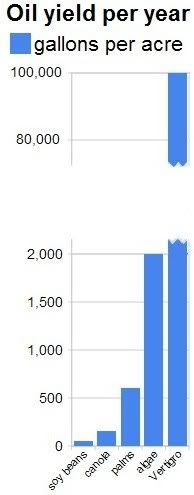

Apart from growing algae in greenhouses, we should also consider growing them in bags. NASA scientists  The NASA article conservatively mentions that some types of algae can produce over 2,000 gallons of oil per acre per year. In fact, most of the oil we are now getting out of the ground comes from algae that lived millions of years ago. Algae still are the best source of oil we know.

In the NASA proposal, there's no need for land, water, fertilizers and other nutrients. As

The NASA article conservatively mentions that some types of algae can produce over 2,000 gallons of oil per acre per year. In fact, most of the oil we are now getting out of the ground comes from algae that lived millions of years ago. Algae still are the best source of oil we know.

In the NASA proposal, there's no need for land, water, fertilizers and other nutrients. As

A 2007

A 2007