The difficulties

When John Nissen first raised the problem

of Arctic methane my initial reaction was that capture at the sea bed would be

impossible. But trying to design for the

impossible can be interesting. It seemed

a useful exercise to identify the reasons for impossibility. We can list

difficulties as follows:

- Methane release at very low flow rates over too wide an area.

- Release at very high rates over a small area such as a well

blow-out.

- Rough seas during deployment.

- The presence of obstructions such as wreckage, rock outcrops,

munitions or steep slopes.

- Fast, variable-direction or unpredictable currents.

- Equipment sinking into very soft ooze on the seabed.

- Hydrogen sulphide toxicity.

- Unacceptable biological consequences due to the presence of equipment.

- The need to recover everything at some date in the future.

- The pressure ridges shown by Peter Wadhams at the Chiswick

workshop.

I now believe that despite these problems

methane can be captured in quite large quantities from areas of several square

kilometres of plastic film in a single installation.

The design

The film sheet is packed into a pair of

left and right-handed rubber trough cases [1] and [2] with a rectangular inner

section as shown in figure 2. Each trough case carries two steel cables [3]. The trough cases would be produced by a

continuous moulding/extrusion machine in lengths of several kilometres using

plant similar to that used for electrical cables. The left and right handed

pair are connected at the centre by two thin isthmus strips of material [4] [5]

above and below a rectangular section passage.

The passage contains a rectangular section runner [6] with two blades

[7] [8] which can be pulled through the full length of the extrusion by a steel

cable. [9]. If the steel cable is pulled the two blades

will cut the connection strips and the trough case halves will be

separated.

The underside of the trough case extrusion has a moulded tread

with a pattern of saw-tooth section ridges [10] lying at an angle of about 30

degrees to the length of the extrusion. This ridge angle is an important design

parameter. At the outer corners of the

bottom of the insides of the trough cases are recesses [11] into which a bead

on the edge of an extruded plastic sheet can be pushed. The outer walls of the trough are much

thicker than the inner walls and contain galleries [12] along which methane can

be transported to riser pipes. They connect to the higher points of the

saw-tooth moulding. A high-density filler is added to the rubber to make sure

that it is heavier than cold sea water but not heavier than the ooze on the sea

bed. The outer edges of the extrusion [13] are sloped like the front of a

sledge.

At the bottom of figure 2 the troughs are

shown filled with a zig-zag stack of flexible plastic with a density just

greater than cold sea water and a thickness of about 200 microns. The zig-zag stacks on each side a joined at

the top [14]. The lower edges with a

bead are pushed into the recesses in each trough. This plastic would be produced by a second

extrusion machine consisting of interdigital plates to be described later. If the width of each trough is one metre and

the trough depth is 150 mm there will be space for 750 layers of zig-zag

plastic, giving an extended width of 1.5 kilometres when the zig-zags on the

two sides are unpacked. The stacks of

plastic film can be packed securely by lid flaps [15] retained by a vacuum

maintained through pipes [16].

The length of plastic and rubber would be

wound in a single scroll on the drum of a pipe-laying vessel such as the Stena

Apache. A drum diameter of 35 meters

could take a width of 1.5 kilometres and length of 3 kilometres, giving a capture

area of 4.5 square kilometres.

Figure 2. Empty and filled extruded rubber trough cases with 4 times enlarged views of end and centre.

Deployment.

Survey vessels with side-scan sonar and

methane detection sensors would look for suitable sites with no large obstructions,

suitable current velocities and comfortable methane emission rates.

Small obstructions can be levelled with

robotic sea bed vehicles such as the one described at the 2011 EWTEC

conference.

The pipe-laying vessel would take station

well downstream of the target area and pay out the scrolled material to the sea

bed as if it were oil pipe. The extreme

flexibility of the trough case (relative to 12 inch steel pipe) would allow

wave tolerant J-lay rather than an S-lay release.

Once the full length of the package is on

the sea bed (figure 3) it would be towed along the seabed by ropes attached to

the fore end of the rubber extrusions until it reached a point before the start

of the target area equal to the string length divided by the cosine of the

ridge angle. If possible the tow

direction should be perpendicular to current and swell.

The central cable with knife blades would

be pulled through the rubber extrusion to separate the two troughs.

The vacuum retaining the lid flaps will be

released.

Towing to increase the width of the film

can now begin. Towing from the pipe-laying vessel would mean lifting the

leading edge of the pack and there might be disturbance by waves. It is preferable to use a horizontal force

from a sea bed walking vehicle. There

might sometimes be an advantage in raising and lowering the leading edge in the

way used for aligning carpets. The tow

force would depend on the weight of the package in water and the coefficient of

friction to the sea bed. This is expected to be about 250 kN. This will set the size of the steel cables

embedded in the rubber extrusions which transmit the tow force along the length

of the rubber and the bollard pull of the tow vehicles.

The tow vehicles will keep the tow lines

pointing along the line of the package but the angled ridges would make the two

troughs move apart from each other and so the tow vehicles will take diverging

courses. The layers of plastic film will be pulled away from the zig-zag stack,

as shown in figure 3, with the weight of the retaining lids providing a gentle

resisting force.. GPS systems will be used to keep the advance rate of the tow

vehicles matched.

The small density difference between

plastic and sea water will mean that the drag friction between plastic and sea

bed will be very low with a factor of safety of several hundred relative to the

plastic strength.

The ridges in the rubber extrusion will

leave furrows on the surface of the seabed.

When the furrows are covered by the plastic sheet they will form

passages for the removal of gas through galleries in the outer walls of the

trough.

The outward movement of the trough cases

will build up material from the sea bed at the front of the outer sledge

faces. Water moving through eductor jets

[17] can move some of the sea bed material over the film.

The gas pipe connection from below the film

to the surface will bring its pressure closer to atmospheric. Eventually several bars of water pressure

will clamp the film and trough casings firmly to the sea bed.

Figure 3. Deployment of the film using the side force

from the inclined ridges at the bottom

of the trough cases. Proportions are grossly

distorted.

Tooling

Thermo-plastic films can be made by heating

pellets of the feed stock to their melting point, pumping the liquid material

through fine gaps in an extrusion tool and progressively cooling the downstream

section of the tool to a temperature at which the film can be handled. The

energy requirement is the sum of melting heat and pumping pressure. Much of the heat can be recycled back to the

incoming feed stock. The product is easier to handle if the pumping is in a

downward direction.

The tool will consist of one inner and two

outer stacks of plates each of which consists of two half plates which have

been machined with a zig-zag coolant channel and then riveted and spot-welded

back together as shown in figure 4. The

key problem is maintaining an accurate gap, probably 200 microns, between inner

and outer plates. Gravitational sag will

be avoided if plates are vertical. At

the top of the tool where the film material is still liquid the gap can be

defined by streamlined shims but in the cooler regions it must be actively

controlled with no physical blockage.

Material from a rolling mill usually has

quite large flatness errors and a skin under compression. The first step will be stress relief by

raising the plate temperature to 650 C for an hour and cooling it slowly.

Toolroom surface grinders can work to a

flatness better than 3 microns but if curved parts are held flat on a magnetic

chuck the curvature will be restored when the magnetic flux is removed. It will be necessary to hold the plates on a

hot wax chuck as used in the optical industry. It might be useful to consider a low-force

cutting technique such as spark erosion.

Figure 4. A grossly distorted plan view of the topology

of the extrusion tool with exploded parts. A 1500 metre width would require 750

plates rather than eight. Maintaining a

gap for the film thickness is a challenging problem but may be done with

differential temperature control. The tool for a 1500 metre width of film would

weigh about 200 tonnes. If the

differential temperature idea is not feasible, smaller tools could be used but

a way to store and join kilometre lengths edge to edge would be needed.

Temporary coiling looks difficult.

Gap control

We can use an array of capacitance

transducers to measure the gap between plates of an assembled stack. We can cover the surfaces of plates with

resistive heating elements either side of the cooling channels. By differential control of the heating

currents we can control the local curvature of a plate. The coefficient of thermal expansion of

stainless steel is 17 part per million per C degree. A temperature difference of 1C across a 15 mm

plate will induce a radius of curvature of 440 metres. If the width of the heating element is 100 mm

this means a deflection of 11 microns.

A neat way to provide plate deflection

control is to divide the plate surfaces into 100 mm squares with a resistive

layer filling most of the area. The

squares would be connected in series and driven with a constant current from a

high impedance source rather than a constant voltage. The current would be diverted around the

heating element by a parallel, high-frequency switch operated for a variable

fraction of the time. A small fraction

of the surface with a grounded guard backing would be given a high-frequency

excitation to measure the capacitance to the adjacent plate.

Cold heat exchanger fluid will be pumped

into the bottom of the vertical tooling plates and emerge from the top at nearly

the melting temperature of the plastic film.

After some extra heating the fluid will then move downwards through a

vertical-tube heat-exchanger to melt the incoming plastic.

Solidified film coming out of the bottom of

the tool will be further cooled by an upward flow air which will then be

directed down through a bed of rising feed pellets and shredded plastic being

recycled. Air can flow easily through

gaps between pellets or shredded feed stock.

The surface area of pellets is large even if heat transfer per unit area

is low. Heat can flow more easily between liquids. However there will be an awkward gap between

solid but nearly molten pellets in the air in the pellet heat exchanger and

liquid in the one above it. Although the

temperature difference might be quite small the amount of latent heat of fusion

might be substantial.

Gas flow rates

A slide (number 34) from the Shakova - Semiletov

paper given at the November 30 2010 DoD workshop in Washington, gives a figure

for methane flux of 44 grams per square metre a day over half a 500 metre

transect, shown below. This is well

above other observations. The calorific value of methane is 55 MJ per

kilogram so this would be a thermal power of 28 MW per square kilometre. These conditions might well not apply to the

full film area and, at this rate, it would probably not be worth collecting

methane on a ship. In future the rate,

and gas prices, might increase. However the power level should be enough to

drive a mechanism with chain saws and heat transfer pipes to keep a clear hole

for a flaring stack in a moving winter ice field if methane release in winter

was thought to be a problem.

Size of release plumes

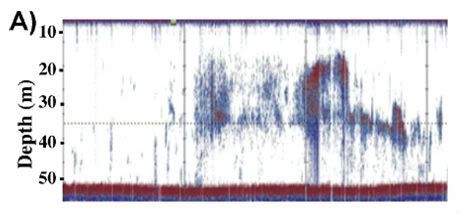

This paper has described what I believe to be the largest possible collector area using present technology. We need to know more about the size and spacing of release plumes to decide if the area has to be as large as this. One example of the kind of data needed is given in figure 5.

Figure 5. An echo sounder image giving the size of

methane plumes from Shakhova et al.. This shows a transect of about 500 metres

in the Laptev sea showing bubble plume return

features

and also zooplankton other non-bubble scatterers such

as fish.

Material quantities

The Shakhova presentation also mentioned total

areas of methane hot spots of 210,000 square kilometres, the area of a square

of side 460 kilometres. The proposed design

needs about 200 tonnes of plastic film per square kilometre. Total world

consumption of plastics in 2010 was about 300 million tonnes and forecast to

rise to 538 million in 2020. Protecting

the Shakova area with coverings which lasted 10 years would take about 1.5% of

total present world plastic production.

Recovery

Maintenance would be very difficult and is

not planned. But anyone putting anything into the sea has an ethical duty to

plan for its recovery. The proposal is

to make structures of two cutting discs about 2 metres in diameter separated at

12 metres which can roll along the length of the film to cut it into 12 metre

wide strips. The ends of the cut can be

gripped with a vacuum plate, lifted to the surface and wound round a drum. The area of the long side of a 3 km length

sheet of clean film is only 0.6 square metres. Over a period of years it will probably have

acquired biological growths, some of which can be removed by pulling it between

contra-rotating brushes. It is desirable

that growth thickness can be reduced to the level at which film can be packed

into 2.2 metre diameter for movement in a sea container. For a film length of 3 kilometres this means

a thickness of film plus growth of 1.25 mm.

The extruded rubber trough cases would be wound on the drum of a

pipe-laying vessel.

Comments on the feasibility of this proposal, however

critical, would be welcome.

Conclusions.

There is a wide range of estimates for the

rates of methane release from Arctic seabeds but the higher ones are alarming

enough for all defensive measures to be carefully examined.

Initial design work for the manufacture and

deployment of kilometre-sized areas of plastic film to capture methane suggests

that that this may be possible for a range of emission rates provided that the

areas of the sea bed are clear of obstructions. This conclusion should be checked

with people from the plastic and rubber industries.

Deployment and recovery will require

pipe-laying vessels from the oil industry , such as the Stena Apache, and

specialised seabed crawlers which have been designed for wave and tidal-stream

installation.

Unless methane emission rates are even

higher than suggested it will not be economical to recover methane for use on

land and so flaring off at sea is more likely.

However there may be enough energy to drive ice-cutting equipment to

keep the water round a flare stack clear of drifting ice in winter.

The extrusion tool for a 1500 metre width

will require about 200 tonnes of very flat stainless steel sheet. The critical

problem is maintaining an accurate gap in the extrusion tool. This can be done with differential

temperature control of opposite surfaces of a stack of interdigital plates with

central cooling channels.

The separation of halves of a film package

can be done by the force generated from angled saw-tooth ridges on the

underside when the package is dragged over the sea bed. This allows very wide film coverage from an

easily transported package and leaves tracks for methane flow.

If the underside of the film has a pipe

connection to the atmosphere the pressure from water above it will clamp it

firmly to the sea bed.

Work on long-term biological testing of

candidate film materials should begin as soon as possible.

It is necessary to have credible techniques

to recover all materials from the sea bed.

The proposed method must be critically checked by experienced offshore

engineers.

A 4.5 square kilometre area of 200 micron

sheet will need about 930 tonnes or 25 railway trucks of plastic but this is

small compared with world production.

Energy consumption in the present plastics industry is about 10 MJ a

kilogram compared with 2.25 MJ for the latent heat of steam. If the film extrusion velocity is 10 mm a

second we will need 3.5 days for one pack and a power of 35 MW. Heat pump technology could give a very large

reduction in energy consumption and must be carefully investigated.

We may have to avoid deployment in water

depths less than the deepest pressure ridges. The leading ice authority, Peter

Wadhams, says that these can reach down to 34 metres below the surface.

Actions

Resolve the three-order of magnitude dispute

about methane release rates and investigate sea bed methane release rates and their

variability in space and time.

Check design assumptions with the plastic

film and rubber extrusion industry.

Choose the best candidate film materials

with density just greater than cold sea water (1028.4 kg/m3) and establish

stress capability in working conditions.

A large strain length is more important than tensile strength.

Place specimens of the various film types

in suitable test site in northern Norway and observe biological

results especially recolonization rates.

The earlier this begins the better.

Albert Kallio has warned about anoxic conditions below the film. The area of test film must be large enough to

replicate this.

Measure tow forces on 5-metre sized blocks

and establish the best ridge angle for a range of sea bed conditions from

gravel to sand to ooze.

Place blocks of various shapes and

densities fitted with accelerometers on the sea bed and measure how many roll

or slide.

Carry out a sonar side-scan survey to

identify obstructions in suitable areas.

Some, such as bullion cargoes, may be removable.

Collect information on depth and occurrence

of pressure ridges in methane release areas.

Pray that the continual underestimation of

the potential climate risks by people who are responsible for defending us

against them does not continue.

Links

World plastic production

Shakhova PowerPoint presentation link.

Shakhova Semiletov paper

Pipe-laying vessels

Other collected papers

References

Dlugokencky, E. J., L. M. P. Bruhwiler, J. W. C.

White, L. K. Emmons, P. C. Novelli, S. A. Montzka, K. A. Masarie, P. M. Lang,

A. M. Crotwell, J. B. Miller and L. V. Gatti (2009), Observational constraints on recent increases

in the atmospheric CH4 burden, Geophysical Research Letters, 36, L18803,

10.1029/2009GL039780.

Frankenberg, C., I. Aben, P.

Bergamaschi, E. J. Dlugokencky, R. van Hees, S. Houweling, P. van der Meer, R.

Snel P. Dol (2011), Global column-averaged methane mixing ratios from 2003

to 2009 as derived from SCIAMACHY: Trends and variability, Journal of

Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 116(D04302), 1-12, 10.1029/2010JD014849.

Montzka, S. A., E. J. Dlugokencky and J.

H. Butler (2011), Non-CO2 greenhouse gases and climate change, NATURE, 476,

43-50, 10.1038/nature10322.

Shakhova et al. estimate the accumulated methane potential for the Eastern Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS, rectangle on image right) alone as follows:

Shakhova et al. estimate the accumulated methane potential for the Eastern Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS, rectangle on image right) alone as follows:  Further shrinking of the Arctic ice-cap results in more open water, which not only absorbs more heat, but which also results in more clouds, increasing the potential for storms that can cause damage to the seafloor in coastal areas such as the

Further shrinking of the Arctic ice-cap results in more open water, which not only absorbs more heat, but which also results in more clouds, increasing the potential for storms that can cause damage to the seafloor in coastal areas such as the

The image on the left shows the impact of 1 Gt of methane, compared with annual fluxes of carbon dioxide based on the NOAA carbon tracker. (10)

The image on the left shows the impact of 1 Gt of methane, compared with annual fluxes of carbon dioxide based on the NOAA carbon tracker. (10)